Deploying Django and Deploying With Django

The other night I was on a panel discussion on Python Deployment at the Django-NYC meetup. The discussion was very good and I think everyone there got a lot out of it (I did). But the format wasn’t really suitable for going into great detail, showing actual code fragments or demos. I’ve written about aspects of our deployment strategy in the past on my personal blog and in comments on other sites, but it’s a continuing work in progress and I’m well overdue for an update. We also have a web-base deployment tool that, while the code has been open and available for a while, we really haven’t officially announced or publicized until now.

There are two angles to Python/Django deployment that I want to discuss. First, there’s deploying Django apps. Then there’s how we use a Django app to deploy Django (and other) apps. They are closely intertwined so I think I can’t really talk about one without talking about the other.

A bit of background. CCNMTL has been around for over a decade, building custom educational software for the Columbia community and beyond. We have six programmers, a couple designers, a dedicated video team, numerous educational technologists, and assorted others. Our projects are of varying size and complexity, but there’s been a fairly steady pace of launches every few months for most of our history. Our technology stack is heterogeneous and has varied over time as well. We currently deploy a number of web applications built on Python (with Django, TurboGears and Plone), Perl, PHP (Drupal, WordPress), and Java. While we may launch new apps every few months, the old ones don’t go away at that rate. Some of the applications we currently maintain have been running for the better part of the last decade in one form or another.

Deploying Django

For deployment in general, we apply Spolsky’s recommendation of a one step build. Deploying an application to production needs to check out the current version of the code from version control, sort out any dependencies, run any build steps needed, run unit tests, get the code onto the production server, and restart or HUP whatever server processes there need poking. If the deployment procedure requires any more manual steps than clicking one button, someone’s bound to mess it up and trouble will not be far behind. Since we have multiple developers and occasionally have to do a quick emergency fix on someone else’s app, it’s extra important that the deployment process be as simple and foolproof as possible. Furthermore, the deployment scripts act as necessarily accurate and up to date documentation on our server setup.

With lots of separate codebases each having potentially very long lifespans, our approach to deployment has skewed very much towards maintaining isolation between the environments. If we need a newer version of a Python library for a new application we’re launching, we simply don’t have the manpower to go through the other 20 applications running on the same server and test that they are going to be compatible with the new version of the library. As much as we can possibly manage, we need to keep them separate and isolated.

We achieve this isolation on a few levels. First, we make heavy use of server virtualization to isolate on a very rough level. We currently segregate roughly based on technology. We have a virtual server for Django apps, one for Plone apps, one for TurboGears apps, one for Perl, etc. This simplifies administration greatly and allows us to tune the performance of the machines differently for different kinds of workloads. We also run several development and staging servers.

What’s more relevant here though is the isolation between Django apps on the same server.

Our Django virtual machine really does currently run about twenty separate applications (I wasn’t exaggerating before). They range from Django 0.96 to Django 1.2. Most of our new applications these days are developed on Django, but we started working in earnest on the isolation side of deployment back when we were doing a lot of TurboGears.

The heavy lifting in this setup is done by virtualenv, which will probably come as no surprise. Mostly what we’ve done is put a nice, cozy layer of conventions on top of virtualenv to make it even more streamlined for our situation.

Another aspect of deployment that we’ve come to a strong opinion about is that deploying to production should not ever depend on anything external. This is a hard won lesson from early TurboGears days. Back when we were using it heavily, TG was a bit of a beast as far as dependencies. It was pretty much the poster child for setuptools and eggs because it had a lot of dependencies. Installing TurboGears or updating it involved setuptools downloading eggs from a dozen different sites around the web. Of course, that practically guaranteed that at any given time, one of those sites would be down, so your install or upgrade would fail. They quickly consolidated and mirrored all the eggs on turbogears.org which improved the situation until tg.org started becoming unstable. Nowadays, I think their requirements are all on PyPI, which is probably an improvement again, but still a potential problem if your deployment hinges on having to download a library. Since PyPI is a common single point of failure for deployments, there’s ample discussion in the Python community about different techniques for making local mirrors of PyPI.

Our approach is simpler than mirroring PyPI though perhaps a bit more drastic. We just check in a copy of every library that the application needs along with it in a ‘requirements’ directory and use a bootstrap.py script that installs all of those requirements (and only those requirements) into a per-application virtualenv. Our bootstrap.py script looks like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python

import os

import subprocess

import shutil

pwd = os.path.dirname(__file__)

vedir = os.path.join(pwd,"ve")

if os.path.exists(vedir):

shutil.rmtree(vedir)

subprocess.call(["python",os.path.join(pwd,"pip.py"),

"install",

"-E",os.path.join(pwd,"ve"),

"--requirement",

os.path.join(pwd,"requirements/apps.txt")])

It’s brutal but effective. First, it does an “rm -rf ve” to clear out any old virtualenv directories so we can make sure we’re starting fresh. Then it does

python pip.py install -E --requirement requirements/apps.txt

Which creates the new virtualenv in ve and installs the libraries listed in requirements/apps.txt, which is a just a text file listing one .tar.gz per line corresponding to the tarballs in the requirements/ directory. Those libraries in requirements/ are everything. Even the Django tarball goes in there. It seems a bit wasteful to duplicate all of those tarballs on every application we run, but it’s a trade-off we’re happy to make. Ultimately, each requirements directory comes in around 20 to 30 MB, which is pretty small in the scheme of things and git has no trouble handling them.

[This is basically what pip now does with its freeze command. We had our system working before pip added freeze though and it works for us so we haven’t gotten around to switching to pip --freeze yet, but we will soon.]

That explains the bulk of how we keep our deployments isolated and not dependent on any external sites like PyPI. In practice though, there are a number of small details that make it actually come together nicely.

We use a custom CCNMTL-specific Paste template to start new Django projects and it plays a big role. Python Paste Templates fill a role similar to django-admin.py startproject. They will create a directory structure for you and pre-populate it with a number of files, some of which have been generated from templates with project specific bits filled in. The advantage is that Paste Templates are pretty easy to create and customize for your situation.

So we have a Paste template called ccnmtldjango which is up on github and you can check it out. A lot of the customizations we use it for are related to how we bundle dependencies for our isolated deployments.

When you run paster create --template=ccnmtldjango, and tell it your project name, it sets up the directory just like django-admin.py startproject would, but it also includes that bootstrap script, a local copy of pip.py, a requirements directory loaded with tarballs for Django and all the libraries that we typically use, as well as sample apache config files that are set up with all the correct paths and configurations so the application can be deployed directly to our production server (Apache and mod_wsgi) with virtualenv isolation fully in effect.

Another easy to miss customization it does is to change the first line of manage.py to #!ve/bin/python. Since most commandline interaction with django involves ./manage.py some command (runserver, shell, syncdb, etc), this saves us from pretty much ever having to “activate” the virtualenv.

The whole process of a developer starting a new Django project is pretty simple. They need to start on a machine with virtualenv, python-paste, and ccnmtldjango installed. Then they run the paster create --template=ccnmtldjango, go into the new project directory, check it into version control, run ./bootstrap.py, and from then on, ./manage.py ... works and is isolated from anything else that might be on the system. When they later push it to production, the dependencies are all right there and the deployment scripts can run ./bootstrap.py on the production server and they are guaranteed to have the exact same versions of every library in production that they had in development.

Deploying with Django

The second half of this topic for us is the application that we use to deploy our Django apps, as well as our TG, Plone, Perl, PHP, and Java apps.

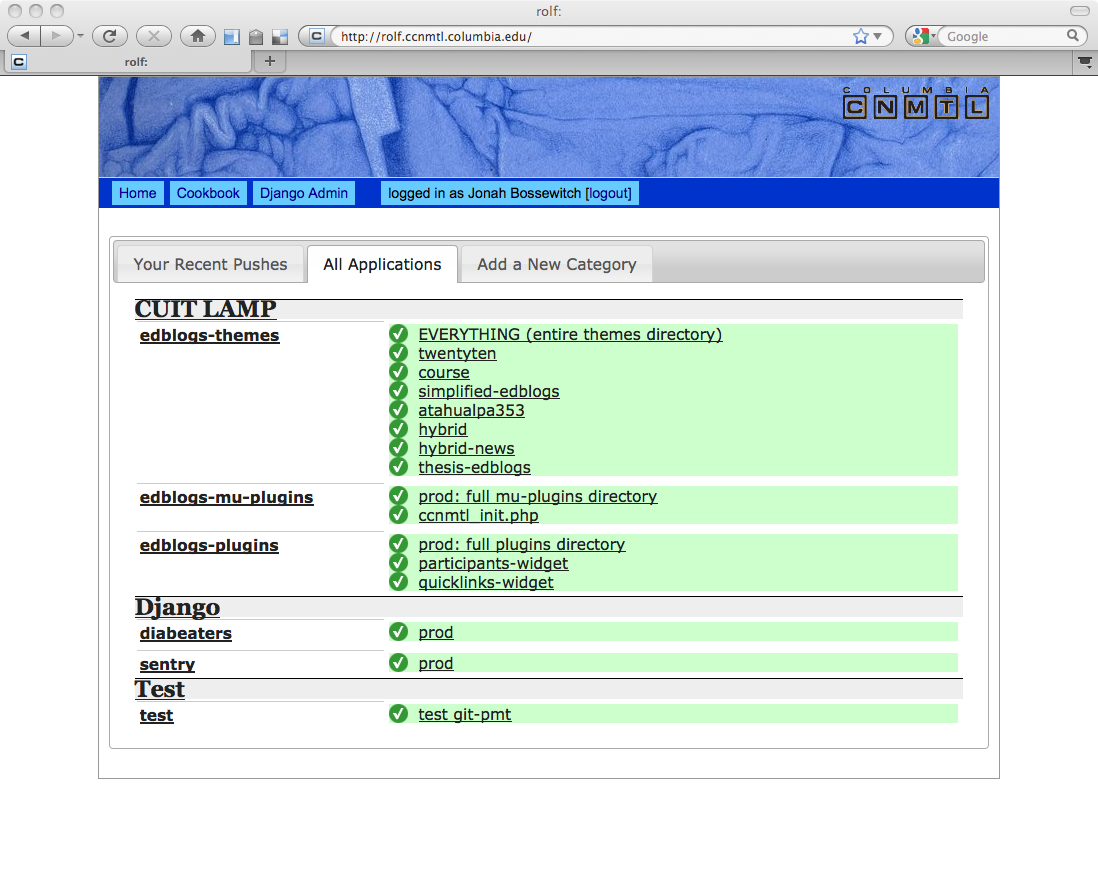

This application is Rolf. Rolf is our web-based deployment system. It happens to be written in Django, though previous incarnations were TurboGears and CherryPy based. Rolf is available on github.

Rolf and its predecessors are our attempt to unify all of our deployment in one place with one reasonably nice interface.

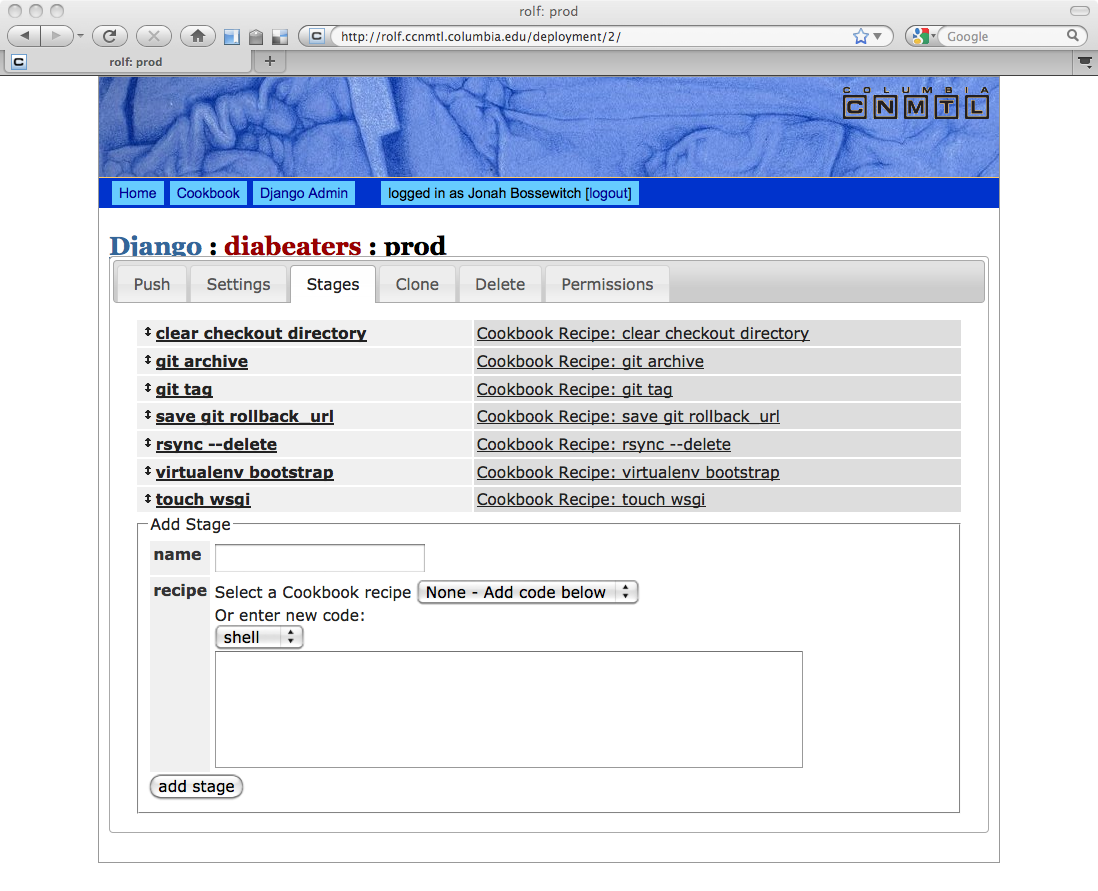

Rolf organizes our projects into individual deployments, which each have a number of stages. E.g., the typical deployment process for a Django app is to clear out the local checkout directory, pull a copy of the app out of our git repo, tag it (so we can roll back to that point in the future easily), rsync the code to the production server, run the ./bootstrap.py step (explained above) on the production server to get all the libraries installed in a virtualenv, and then touch a .wsgi file (which causes Apache to reload the code for that application).

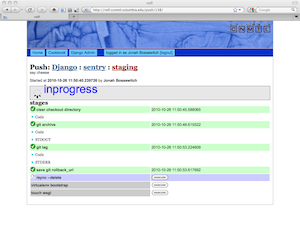

Rolf lets a user kick off that process through a nice, AJAXy web interface. As each stage runs, it logs everything that happens on STDOUT and STDERR and will halt the push if any of the stages fail. All the pushes are logged and saved, which comes in handy for forensic analysis. If a push is successful, it saves the tag for that push and allows a user to roll back to that particular tag easily should a future push break.

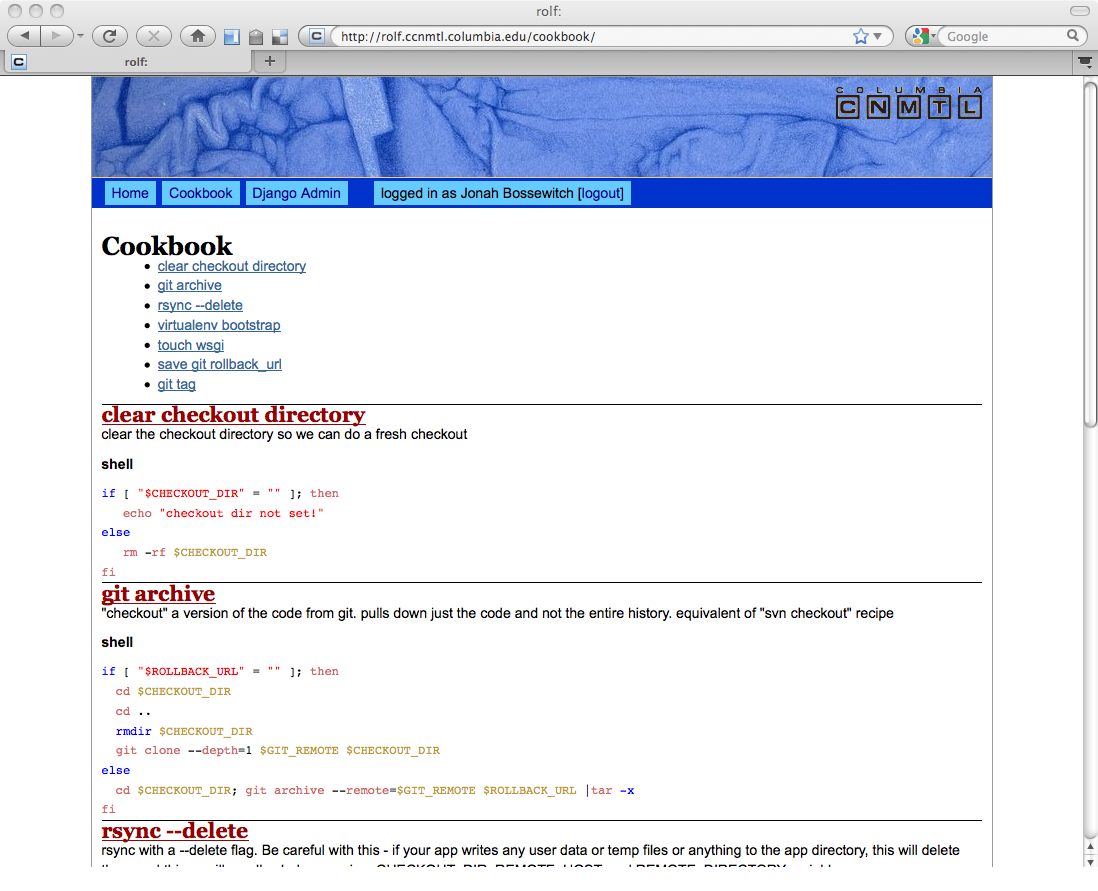

Each stage can be written in Bash or Python. They are typically one or two command “recipes” using environment variables to stay generic so they can be used across multiple deployments. Rolf also includes a “cookbook” area to collect the useful, re-usable recipes.

Rolf has fairly basic permissions, but it’s enough to support a couple use-cases that we like. Our install of Rolf sits behind Columbia’s central authentication service, which also provides us with the list of unix groups of each user, which we map to Django auth groups. We can then assign group permissions for each deployment. A group can have view, push, or edit permissions for a deployment. The developers and admins will get edit permissions so they can change the settings and edit the recipes for the stages of the deployment. Designers who often need to push an app out to production but shouldn’t have to worry about the settings or stages are granted push permissions. Project managers probably only need view permissions so they can see if bug fixes or features they’ve been monitoring have been pushed to production yet. Meanwhile, anyone not affiliated with the project can be locked out.

This whole combination of tools gives us a very powerful, flexible system for us to deploy a large number of independent applications with minimal pain and suffering for our developers. This lets us focus less on the nuts and bolts of deployment on a daily basis and concentrate instead on developing unique educational tools.