On Hold

Laura Poitras / Praxis Films

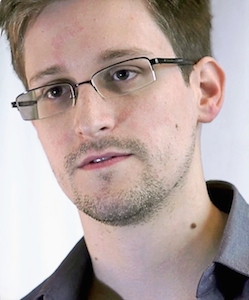

Edward Snowden

Throughout Wednesday, Gellman held several conversations with his government contact. They had arrived at an impasse. We flat out disagreed on the biggest ask the government made for this story, Gellman recalls. They did not want the Post to publish the names of the nine US Internet companies. Asked why, the official explained that disclosing the names might lead the companies to stop cooperating. Gellman stood his ground. If the governments definition of harm was that the companies might change their policies in response to objections from customers, Gellman regarded that as more reason to publish. Gellman suggested that the official call Executive Editor Baron if he wanted to plead the governments case at a higher level. Youre welcome to go straight to the top on this one, Gellman told him. It was standard practice at the Post for reporters to handle official comments on their own stories; editors became involved only if the government approached the paper. The official asked for more time to consult inside the government.

The next day, Thursday, June 6, Gellman, exhausted and stressed, accidentally contacted Snowden on the wrong channel, alarming him. Snowden by this point was jumpy. He told Gellman that police had showed up that morning at the house he had occupied until recently in Hawaii. Gellman told him the story would post online that day.

Gellman had given his government contact a deadline of Thursday afternoon to make any final requests or arguments. He wondered whether the White House would indeed call Baron or Post Chairman Graham. By then, Gellman was no longer ensconced on the seventh floor. He had moved to the fifth floor newsroom, where he either huddled with Leen in his glass-walled office, going over the storyfinally on the newspapers serveror sat in the newsroom talking to his government contacts.

At Leens urging, Gellman had written most of the story. The company information could be dropped in at the last minute. Leen did not want to pressure Gellman, but he, too, wanted to publish. Leen had to walk a fine line with Gellman: get what you need, but work as quickly as possible. Its not easy to do these [investigative] stories on deadline, says Leen. We knew we were in a competitive situation to get this story.

Leen on deadlines and competition

While Gellman waited, he made a final review of the governments arguments against publishing the company names. The government has told you: you shouldnt name these companies because itll harm the governments relationship with those companies in a secret program, he recapitulates. Was that the real reason? Or did the government worry that the companies would take a stock market hit? Did the White House fear a public opinion backlash?

Of course the story would run. The public was entitled to know how NSA activities had changed. But Gellman wanted to be responsible and not gratuitously injure national security or needlessly reveal operational details. How could the story and the companies denials be true at the same time? If he did publish the company names, was that really a service to readers? Did the public need to know?