Sprechstimme

A vocal style that combines elements of song and speech.

|

|

|

Fig 1: Performance of Pierrot lunaire (1940), E.Stiedry-Wagner, reciter, A. Schoenberg conducting. |

[Example 1: Schoenberg: Pierrot lunaire, No.8 "Night", CD1784.]

Sprechstimme is a vocal style that combines elements of song and speech. Like a conventional vocal melody, Sprechstimme uses musical notation that indicates rhythm and pitch. But instead of singing the pitches, the performer recites them. We can hear what this sounds like by comparing two versions of "Alabama Song" by Kurt Weill (1927). The first one utilizes Sprechstimme:

[Example 2: Kurt Weill: "Alabama Song," from the Mahagonny Songspiel.]

In that performance, the reciter reproduced the rhythms exactly, but only approximated the pitches, which is precisely what Sprechstimme calls for.

The vocal part of Weill's "Alabama Song" was rewritten two years later (1929) as a conventional sung melody for soprano and chorus. You can hear how the voice is now singing the pitches exactly, without any slurring between the tones.

[Example 3: Weill: "Alabama Song" from Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, CD4462.]

[Fig 2: notation of Sprechstimme from Pierrot lunaire, No.9.]

|

|

|

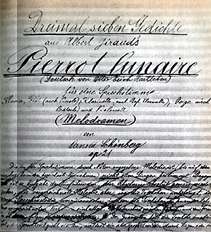

Fig 3: Title-page of Pierrot lunaire |

Sprechstimme was used most frequently during the early decades of the 20th century, especially in Germany and Austria. The technique, which is associated most often with Arnold Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire of 1912, originated around 1900. Schoenberg himself employed it in several other works, including his opera Moses and Aaron (1930-32, unfinished). Other composers who have used it since then include Alban Berg, in his operas Wozzeck (1922) and Lulu (1935), and more recently Pierre Boulez in the late '40s and early '50s -- the latter employing it with the French language.

Sprechstimme arose out of an older genre called melodrama, in which words were declaimed (without musical notation) simultaneously with music. Melodrama developed as a genre in the 18th century (Mozart made use of it), and it continued into the 19th century, occasionally being incorporated into opera. Schoenberg subtitled his Pierrot lunaire as a set of 21 "melodramas," so emphasizing the continuity between this earlier technique and Sprechstimme.

The unique sound of Sprechstimme was often used to represent emotional duress, the macabre, even madness. It is not surprising, therefore, that it appears in music associated with the Expressionist movement, which explored extreme emotional states. Pierrot lunaire (1912) is an Expressionist work, and shares all of these elements, as we can hear in the following excerpt. Notice how Schoenberg calls on the reciter to sing the last three syllables (in italics).

|

|

Finstre, schwarze Riesenfalter |

|

Somber, black giant mothwings |

|

töteten der Sonne Glanz, |

|

killed the sunshine, |

|

|

Ein geschlossnes Zauberbuch, |

|

An unopened magic-book |

|

|

ruht der Horizont -- verschwiegen. |

|

lies the horizon -- in silence. |

[Example 4: Schoenberg: Pierrot lunaire, No.8 "Night", CD1784.]

Finally, here is a quite different use of Sprechstimme. In Schoenberg's Moses and Aaron (1930-32), Moses is deep-thinking but verbally inarticulate, whereas Aaron is highly verbal but shallow-thinking. Accordingly, Moses recites in Sprechstimme; Aaron always sings. In this excerpt -- from the moment when Moses returns from the mountaintop with the ten commandments, and is aghast to see the golden calf -- you can hear the contrast in their dialogue.

|

Moses |

Aaron, was hast du getan? |

|

Aaron, O what have you done? |

|

Aaron |

Nichts neues! Nur was stets meine Aufgabe war; Wenn dein Gedanke kein Wort, mein Wort kein Bild ergab, vor ihren Ohren, ihren Augen, ein Wunder zu tun. |

|

Nothing different! Only my job: When your thoughts gave out no words, my word gave no image to make their eyes and ears marvel. |

|

Moses |

Auf wessen Geheiss? |

|

On whose orders? |

|

Aaron |

Wie immer: ich hörte die Stimme in mir. |

|

As always, I heeded the voice within me. |

|

Moses |

Ich habe nicht gesprochen. |

|

I gave no such instructions. |

[Example 5: Schoenberg: Moses and Aaron, Act II, Scene 5, CD202.]

Summary:

- Sprechstimme is a vocal style that combines elements of song and speech.

- It was used most frequently during the early decades of the 20th century.

- It was often (but not always) used to represent emotional duress, the macabre, or madness.

|

Sprechstimme written by: Michael Von der Linn

Recording & Mixing: Christopher Bailey Narration: Mark Burford Producers: Ian Bent, Maurice Matiz |