- Title Page

- Introduction

- No Child Left Behind

- School Choice in Chicago

- A Beat Reporter Goes Deeper

- Going In Blind

- First Day, First Twist

- Beginnings of a Theme

- Behind the Scenes

- First Month at Stockton

- Obstacles

- From Stockton to Attucks

- Salvaging a Story

- The Projects Team

- Third Chapter?

- How to tell her?

No Child Left Behind

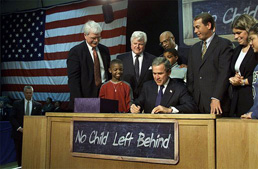

President George W. Bush signs NCLB into law

at Hamilton High School in Hamilton, Ohio, on January 8, 2002.

Courtesy The White House.

President George W. Bush signed the law intended to help children like Rayola Carwell on January 8, 2002. The No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) was technically the latest reauthorization of the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). But by 2001, there was bipartisan consensus that too many children were able to graduate from high school without the skills necessary to compete in the 21 st century. NCLB broke new ground with its insistence that any state which accepted federal funding for education test children in public schools on their mastery of reading and math. The law, as President Bush put it, took aim at “the soft bigotry of low expectations.” [1]

Every school had to make measurable yearly progress in meeting its state’s reading and math standards, or face sanctions. Students would be tested annually from third through eighth grades, and at least once in high school to ensure that they were learning the basics. School results would be made public, thereby holding schools accountable to parents and the communities they served. If a school failed to improve, it would be given additional funding for individual tutoring and other measures to boost students’ performance. If, after two years, a school failed to improve scores, its students could transfer to a better school; after three years, if no transfer was possible, students were entitled to free after-school tutoring. After four years of flat or declining test scores, the government could force a school to make significant changes, including firing underperforming teachers.

However, because education was a state right, not a federal one, the law did not establish national performance standards nor even a national test. Rather, each state was left to create its own standards and tests. Until states could meet the 2005 deadline for creating new guidelines and tests, they were expected to rely on existing standardized tests to determine which schools needed to improve.

Choice . In a part of the new law known as the “choice provision,” NCLB also gave parents greater say in their children’s education. Parents of any child enrolled in a school that failed to meet state standards for two consecutive years could transfer the child to a better public school in the district, which would have to provide transportation. Children in dangerous or violent schools were given the option of moving to a safer school in that district. [2]

Pros and cons . From its inception, NCLB drew both support and criticism from across the political spectrum. Supporters saw it as a long overdue effort to set high standards and create real incentives for schools to meet them. [3] Newsweek ’s Jonathan Alter spoke for many when he praised the fact that test scores would be broken down to see how minority groups perform, “ instead of hiding their lagging test scores in larger averages. This will force even successful suburban districts to focus more on minority achievement, which should increase pressure to improve remedial classes across the board.” [4]

Critics, however, worried that the law would fall short of its ambitious goals—in large part because states were free to devise their own tests. That created a temptation for states to do better not by improving the quality of their schools, but by setting lower standards. [5] There was also a fear that some schools would try to maintain high standards by limiting the number of underprivileged and minority students. [6] Finally, skeptics predicted that teachers, to ensure their students scored well, would “teach to the test” and neglect subjects the test did not measure, such as art or social studies.

But the choice provision drew little criticism. Who could object to moving motivated students to better schools?

[1] As quoted in “ Education Reform Left Behind ,” New York Times , February 8, 2003.

[2] States were responsible for creating guidelines to determine which schools were dangerous. “ Four Pillars of NCLB ,” US Department of Education, Accessed March 10, 2009.

[3] Chester E. Finn, Jr., “Leaving Education Reform Behind,” The Weekly Standard , January 14, 2002.

[4] Jonathan Alter, “ Give the Pols a Gold Star ,” Newsweek , January 21, 2002.

[5] In fact, at least one state, Missouri, lowered its standards after the law went into effect. Nancy Zuckerbrod, “Congress to Weigh ‘No Child Left Behind,’” Associated Press , January 13, 2007. A 2007 study by the Northwest Evaluation Association found a wide disparity in the proficiency standards set by various states. G. Gage Kingsbury et al, “ The State of State Standards: Research Investigating Proficiency Levels in Fourteen States .”

[6] James E. Ryan, “The Perverse Incentives of the No Child Left Behind Act,” University of Virginia School of Law, 2003 Public Law and Legal Theory Research Papers. December 9, 2003.