The Next Step

With her editor’s approval, Sullivan started the research she wished she had done before contacting the prison spokesperson. She read the case files about the two prisoners and news stories about the murder and trial. She searched LexisNexis—an online database of more than 40,000 news, legal, and business stories—for every clip related to the prisoners dating back to 1972, the year of the crime that landed them in solitary.

She learned that on the morning of April 17, 1972, Brent Miller, a white 23-year-old corrections officer who was born and raised in Angola, was stabbed 38 times with a lawn mower blade during his shift at a prison dorm and died. These facts, Sullivan learned, were among the few not in dispute. Eventually, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox—two African-Americans each already serving 50-year sentences (Wallace for bank robbery; Woodfox for armed robbery)—were named as the prime suspects based on an eyewitness account from Hezekiah Brown, a serial rapist with a life sentence. Following their trial by an all-white jury and swift conviction, the two men were sentenced to life in prison and placed in solitary confinement.

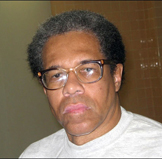

Albert Woodfox.

But from the start, there were doubts about their guilt—and about the evidence used to convict them. Some of the 200 inmates interrogated by prison officials later claimed their questioners had used tear gas and beatings to extract evidence. Then there was the credibility of the star witness: Brown. The rapist had initially said he knew nothing; only in subsequent statements did he—and prison officials—maintain that he’d witnessed Miller’s murder. His fellow inmates considered him a “professional snitch.” Months after the murder, four more witnesses stated they saw one to four men running from the murder scene, yet none of these witnesses apparently had seen one another. The grand jury that indicted Woodfox had not included a single African-American or woman. Nor had his lawyer used this fact to motion for dismissal of the case. Such evidence had persuaded a judge in 1992—fully 20 years later—to overturn Woodfox’s conviction and call for a fresh trial (the judge did not, however, release Woodfox either from Angola or from solitary pending a new trial). [1]

Herman Wallace.

As Sullivan unearthed more evidence about the case, she began to wonder whether Woodfox and Wallace had been wrongly convicted. There were numerous red flags. For example, in 1993, prosecutors won a second indictment against Woodfox. But one member of the grand jury that re-indicted Woodfox was Anne Butler. Butler was the former wife of an Angola warden, C. Murray Henderson, who had headed the Brent Miller murder investigation in 1972. In 1992, the then-couple (they had since divorced) published Dying to Tell , a book on Angola that included details about the murder and stated confidently that Woodfox and Wallace had committed the crime. During grand jury selection for the pretrial hearing, Butler again stated she believed Woodfox was guilty and told the district attorney that perhaps he should remove her from the jury. He did not.

That Butler had written the book was not a problem. But in an interview, Butler told Sullivan what she had said during jury selection and added that she had brought the book with her and distributed the book chapter about Woodfox to her fellow jurors during the grand jury proceedings. This, Sullivan knew, meant Butler had tainted the jury. Members of a jury are supposed to base their indictment or verdict solely on evidence presented during case proceedings and are prohibited from reading or watching anything about a case.

In the 1998 retrial that followed (a full six years later), a jury had re-convicted Woodfox of murdering Miller. But this conviction had also raised questions. During his testimony at the second trial, Angola Warden Henderson admitted to promising Brown, the serial rapist, a pardon in exchange for a statement saying he witnessed Woodfox and Wallace murder Miller. Sullivan, when she looked into this, found proof in prison records that Henderson had in fact written numerous letters to state officials requesting a pardon for Brown. Apparently, this had not deterred the jury from conviction.

In its own way, however, the system had not neglected the prisoners. As was the practice with all solitary confinement cases in Louisiana, the warden reviewed Woodfox and Wallace’s punishment every 90 days and decided whether to renew it. For reasons which the wardens had not been required to document, their status had remained the same for 36 years. Because the wardens believed the two men were dangerous, they spent 23 hours a day in windowless concrete cells. During the remaining hour, they were allowed a walk to the shower; every three days, they had an hour in a small caged exercise pen outdoors.

Prisoners’ support. One of the calls Sullivan made was to a prisoner advocacy group called “Free the Angola Three.” Prisoner advocacy groups, she knew, were often inadequately funded organizations, sometimes run by as few as one or two people who wanted to keep a prisoner’s case in the public eye and aid in his or her release. The name of the group confused Sullivan. She had heard of only two, not three, prisoners being kept in solitary confinement in Angola. It turned out that the third prisoner was another case entirely. The advocacy group believed that Wallace and Woodfox were innocent.

The group gave Sullivan multiple interview leads and copious information about the case. With time, however, the relationship became somewhat difficult. “I felt like they were exerting a sense of control that did not belong to them over my reporting in this story,” she says. “I did not feel like I owed them any sense of what I was doing, what I was working on, who I was talking to in the interviews. And it became clear sort of halfway through that they expected that, that they wanted… to control what we were learning as well.” Apparently, the advocates were worried that Sullivan might uncover evidence of the inmates’ guilt, not innocence.

They need not have worried. From one of the prisoners’ current lawyers, Nick Trenticosta, Sullivan learned additional details about the various twists and turns of the case over the years. Like the advocacy group, Trenticosta believed the two men were railroaded. After interviewing him, Sullivan knew her story was no longer just about two men held in solitary confinement for the longest period in US history, but about a possible miscarriage of justice. “I knew that I wanted to explain the case, bring it to life. I just thought it was this very compelling story,” she says.

[1] Woodfox v. Burl Cain, Warden, Louisiana State Penitentiary, Angola, LA, Case no. 68933, filed in 21 st Judicial District Court, Parish of Tangipahoa, State of Louisiana, p.2.