Earthquake and a strategy rethink

Late on the afternoon of January 12, 2010, Levy, Fischer, Morton, and several other UNEP staff had finished a series of meetings in Port-au-Prince. They decided to stop at the UNEP office, located in the UNDP compound, before going back to the Hotel Montana where they were staying. Meanwhile, Wah and a research assistant had stopped by Wah’s apartment in Port-au-Prince on their way to a meet a group of Columbia University students at the same hotel. Wah got a call: the students were headed to the UNDP office instead. Then, at 4:53 p.m., a magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck 10 miles southwest of Port-au-Prince. [18] At Wah’s apartment, “everything shifted,” she recalls.

It just moved all at once: the dressers, the desk, the dining room table. We thought at first it was just a bomb, and then it kept going. We couldn’t get out. [Eventually] we had three guys hold these stairs for us to escape from the house. The stairs were shaking. Every split second there was a shake.

Wah and her assistant walked to the UNDP compound to find Levy, Fischer and the other Columbia University students, who were helping move injured people from the UN Headquarters. The building had collapsed and killed 84 of the UN staff. “It was horror everywhere," she says.

It was as if everything was bombed. White soot was everywhere, from the horrible cement that these houses were built on. Everybody was covered in white all over, and everyone was huddling together and praying. That was all we saw for miles.

The UNDP office in the UN complex withstood the earthquake; Levy, Fischer, Morton and their team were unhurt. They were lucky. “Normally at that time of day, it would have been a coin toss as to whether we go back to the Hotel Montana or go back to the office,” notes Levy. “And luckily we went to the office because the Montana, very few people survived that. The whole place just collapsed.” [19] The steep hillsides around Port-au-Prince meant that numerous buildings, like the Montana Hotel, slid off their pillars and down the slopes.

The earthquake destroyed thousands of structures in the capital, including the presidential palace. Estimates of the dead ranged from 46,000 to 316,000. [20] One and a half million people were displaced, creating an internal refugee crisis. Losses were estimated at $8-$14 billion. [21] The Reuters Thompson Foundation called it the biggest urban disaster in modern history. [22]

Higher priorities. Work on the Haiti Regeneration Initiative and the Millennium Village Project was put on hold as all available resources went into helping Haiti recover from the earthquake. "My first thought was, my job changed," says Wah. "I can’t even mention MDGs or MVPs when 300,000 people have just died." Even if Wah had wanted to pursue the Millennium Village Project, there was no one in the government to work with. All 18 of the Government of Haiti’s national ministry headquarters had collapsed (the regional offices were not damaged). In the Ministry of Planning alone, 36 people died. "The top managers who I had been talking to were no longer there," she says.

Prime Minister Jean-Max Bellerive had been in office only two months when the earthquake struck. On April 15, the Haitian parliament approved the Interim Haiti Recovery Commission (IHRC) to coordinate relief efforts. Bellerive and former US President Bill Clinton were co-chairs. (Together with former President George W. Bush, Clinton also launched the Clinton-Bush Haiti Fund to raise funds in the US.) Wah, who had represented Haiti’s interests in the design of the IHRC, was named its director of strategy and planning.

The international community and the government of Haiti also created the Haiti Reconstruction Fund (HRF), which pooled and distributed funds for rebuilding. The UN, World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank were authorized to draw from the fund to finance specific projects. The IHRC would receive and vet project proposals, then submit approved proposals to the HRF for funding.

Reverse migration . The earthquake had displaced hundreds of thousands from the capital, increasing development pressures in rural areas as many returned to extended families in their home regions. Rural communities strained to absorb the influx: more people meant greater demands on already limited food supplies, health services and jobs. The southern coastal areas and mountains had limited capacity to support a growing population. The south already had high food insecurity, serious malnutrition, and weak social services. The region was also particularly vulnerable to hurricanes and flooding. Nevertheless, many people headed south. Wah recalls:

We started with the map of where these people went after the earthquake, because people went back home. And that’s when we started seeing the number of people who went back into the south. It's a very vulnerable place, but people still went back there.

Planners had long grappled with overpopulation in the capital, and slowing if not reversing rural-to-urban migration was a government priority. "[Port-au-Prince] was not built to hold two million people," says Wah. So rather than being sidelined by the earthquake recovery imperative, the south became a key part of the government's recovery strategy. Meanwhile, in February 2010 the UN, with government assistance, conducted a post-disaster needs assessment to put a dollar figure on replacing what was lost, says Wah. But Prime Minister Bellerive didn’t want recovery efforts simply to restore what had been. "It wasn’t built right in the first place," says Wah. "We needed to start over. There was no sewer system or access to safe water or sanitation for most." The government labeled the recovery effort the "refoundation" of Haiti.

In March 2010, the government released a crisis recovery plan that called for four development hubs outside the capital, including the south. The UN's assessment report, together with the government’s recovery plan, led to a donor conference in New York on March 30, during which countries pledged $9.3 billion toward recovery and development.

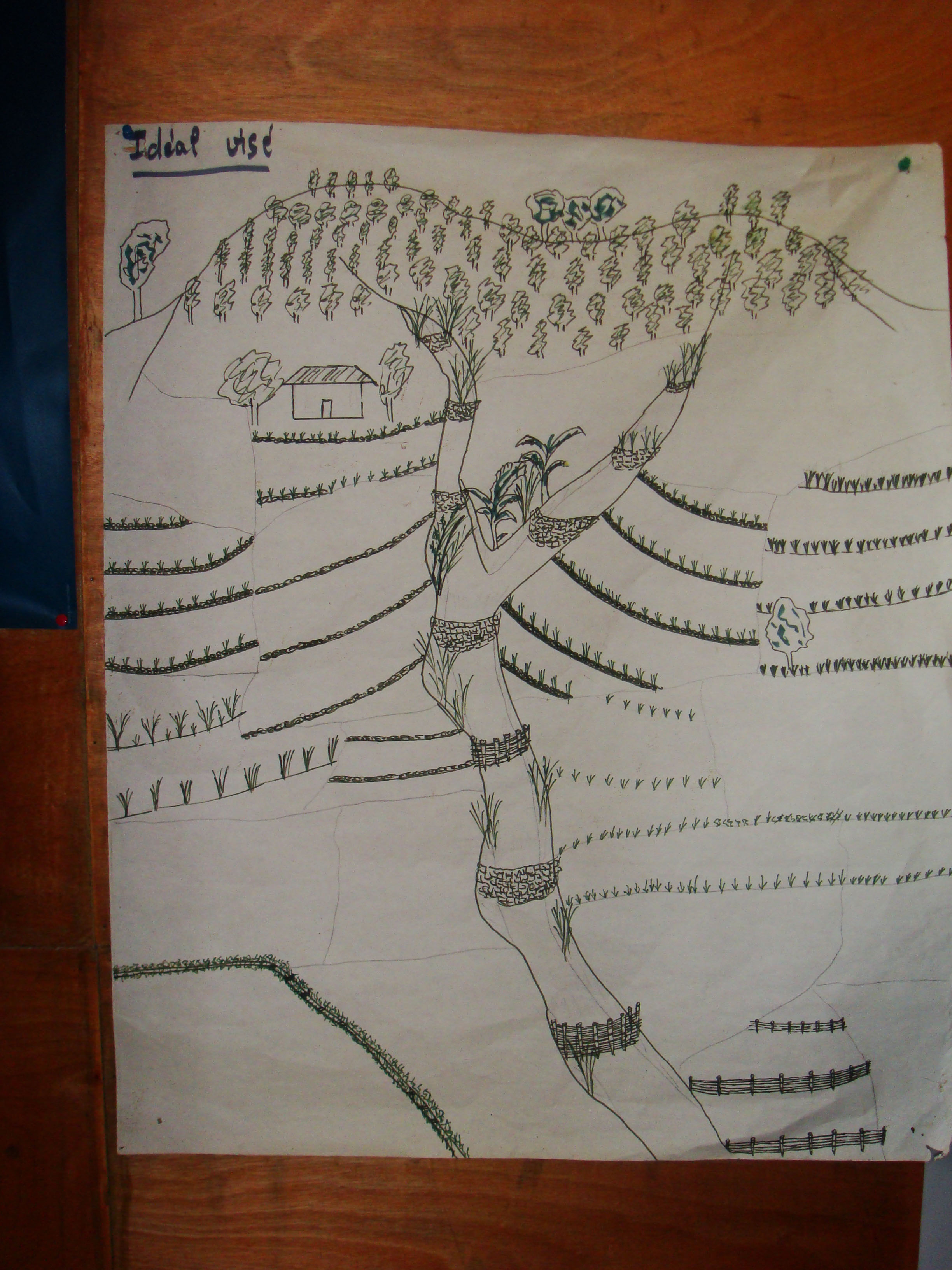

© Columbia Earth Institute

A hand-drawn watershed map with techniques for

using vegetation as anti-erosion infrastructure.

Watershed moment. At the same time, the Earth Institute considered moving the Haiti Regeneration Initiative watershed project to a suburb of Port-au-Prince. "You don’t have to go too far outside of Port-au-Prince [to] get a lot of these same ecological problems: deforestation, flooding, erosion and so on," says Levy. But after the Port-à-Piment municipal government reported a post-earthquake population increase of 50 percent, they decided to stay put.

By spring 2010, UNEP had completed two reports about environmental recovery and poverty reduction with a focus on watersheds. Their analysis showed that international aid projects typically spanned only a year or two. In the reports, UNEP acknowledged that short-term funding would be inadequate for this type of project. “One of the key lessons learned from earlier initiatives in Haiti is that over-reliance on short term aid funding (particularly ad hoc grants of 1-3 years) undermines project impact and sustainability,” said one. [23] The second report concurred. It stated:

The Haiti Regeneration Initiative... is not a conventional project but instead the proposed start of a national scale campaign with a targeted turnover of over 3 billion dollars over a 20-year period. Hence the vision and goals are extremely ambitious and the design and planning process is quite elaborate. [24]

On March 22 and 23, 2010, key players from the government, UNEP, donor organizations and the Earth Institute met in Miami to review post-earthquake thinking on Haitian redevelopment. According to Levy, participants discussed ecological sustainability, decentralized economic development and evidence-based, science-grounded development strategies. The meeting also focused on reducing risks from disasters. Hurricanes, in particular, were an endemic threat, and played a part in landslides and unhealthy watersheds. There had been recent episodes of silt and mud inundating slums around Port-au-Prince after upstream deforestation. "There was no point protecting yourself against earthquakes if all these other disasters were going to kill people," says Levy.

The Norwegian flag

Norway steps up. As part of the influx of international aid following the earthquake, the Norwegian government pledged NK800 million ($127 million) in reconstruction and development aid, with an initial NK200 million ($31.8 million) committed to the Haiti Reconstruction Fund. Norway targeted its assistance to the south—neglected by other donors—with the aim of giving residents reason to remain in rural areas rather than migrate to cities, and to identify pathways to more resilient communities, both ecologically and socio-economically. [25]

For the HRI watershed project, the pieces were beginning to come together: government interest with post-earthquake urgency, a deep-pockets international funder claiming the south as its turf, the UN taking the long view, and the Earth Institute with its scientific approach to sustainable development. The missing piece was an integrated, multi-sector development project. So Levy and Morton approached Wah about joining CSI, and moving the envisioned Millennium Village from the Central Plateau to the south. Wah agreed readily. Such a move dovetailed with the government’s focus on the south and decentralization.

So in March 2010, the combined watershed reclamation project plus Millennium Village became the Côte Sud Initiative, a subset of UNEP’s Haiti Regeneration Initiative. CSI included intensive investment in the Port-à-Piment watershed, and other projects across a 10-county ( commune ) region. The Millennium Village, a geographic subset of the watershed, aimed to bring intensive investment in social services to a small area (the goal was $120 per capita per year).

The Port-à-Piment watershed reclamation portion of CSI was known as the Haiti Southwest Sustainable Development Project. Says Levy: "There was a desperate desire for a proven model of how to achieve sustainability at a watershed scale that was going to be relevant for the entire country, including the immediate environs of Port-au-Prince." With luck, CSI would be that model.

[18] US Geological Survey. See: http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/eqinthenews/2010/us2010rja6/

[19] Next to the UNDP compound was a 7-story building that housed the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), or peacekeepers. The MINUSTAH building collapsed, killing 102 staffers. “By the time I saw them, Marc and Alex were carrying folks on stretchers,” says Wah. “The bodies piled up one on top of another, and just the mess of it all, it was just shocking.”

[20] Maura R. O'Connor, “Two Years Later, Haitian Earthquake Death Toll in Dispute,” Columbia Journalism Review, January 12, 2012 . See: http://www.cjr.org/behind_the_news/one_year_later_haitian_earthqu.php

[21] Reuters Thompson Foundation. See: http://www.trust.org/spotlight/Haiti-earthquake-2010

[22] Ibid.

[23] Haiti Regeneration Initiative Preliminary Concept Note, September 2009, United Nations Environment Program.

[24] Haiti Regeneration Initiative: Study of lessons learned in managing environmental projects in Haiti. See: https://www.cimicweb.org/cmo/haiti/Crisis Documents/Cross Cutting Issues/Environment/UNEP - Lessons Learned in Managing Environmental Projects in Haiti.pdf .

[25] “Norway joins Interim Haiti Recovery Commission,” Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, June 18, 2010. See: http://www.norway-un.org/NorwayandUN/Selected_Topics/Humanitarian-Efforts1/Norway-joins-Commission-in-charge-of-Haitis-recovery-and-development/