Blindsided

After delays in setting up the BEST trial, by the fall of 2007 and winter of 2008 the fieldwork was generating a steady flow of data. Evidence of the antioxidant treatments effectiveness would not be available for a number of years. But Parvez was glad to learn that both the US and Bangladesh data safety and monitoring boards (DSMBs), which kept tabs on the study as protocol required, found the trial was doing its subjects no harm. The filters, provided they were properly maintained and performed as designed, largely eliminated arsenic from water.

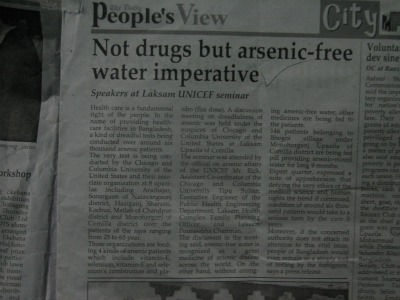

The article accusing BEST of poisoning villagers.

Thus in early March 2008, Haider was surprised when he read a story about BEST in a local paper which cast the clinical trial in a very unfavorable light The English-language Peoples Daily View in Chittagong on March 2 published an article titled Not Drugs, but Arsenic-free Water Imperative. In it, the journalist accused BEST of poisoning subjects with capsules of arsenic-contaminated water.

The article invented several points, including a meetingwhich had never occurredof BEST researchers, a UNICEF representative and engineering and public health officials from Laksam. The story also referred to a press release by the foreignersa press release BEST had never issued. [30] In another newspaper, study participants posed for photographs that ran next to stories claiming the villagers had been poisoned. The villagers later told Haider that reporters and photographers had promised the village new facilities if they would pose for pictures. Haider forwarded the articles to Ahsan and Parvez in the US.

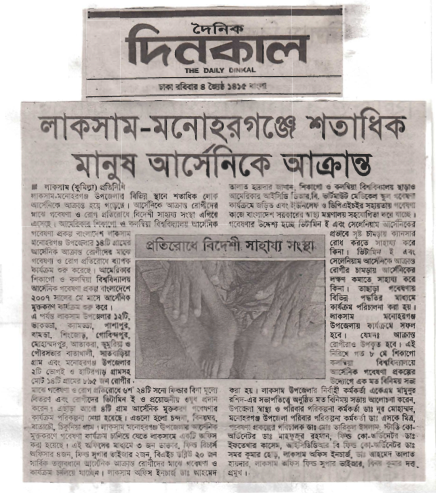

At first, Ahsan and Parvez shrugged it off. It wasnt practical to respond to every misunderstanding, and they thought local staff should be able to handle any fallout. But some of the local journalists also wrote for national publications, which within a month picked up the story. Locally, it was covered by papers like Somoyer Dorpon, Laksam Barta, and Dainik Comilla and nationally by Jai Jai Din , and Dainik Dinkal . The hostile articles included one on March 31 airing charges that BEST participants werent getting promised medical care and were demanding an investigation into Columbia's actions. The articles also claimed that trial subjects had not been given contact information for Columbia officials.

Positive press.

Much of the coverage was negative and sensationalized. Some journalists pointed to the double-blind aspect of the trial as evidence that the researchers "don't know what they're providing," recalls Haider. Not all media took a negative view, however; a number of articles endorsed the project or provided neutral accounts of it. In April and May of 2008, local and national publications carried stories that detailed the extent of arsenicosis in the area and highlighted the projects mitigation efforts. One of these, an article in the May 8 edition of The Daily Dinkal titled Hundreds Affected by Arsenic Exposure; Foreign Organizations Provide Help, informed readers that the researchers were working in 14 local villages, providing participants with free filters and medical screenings. [31] Haider says sympathetic reporters let the BEST team know what was going on behind the scenes in the local media.

Source . That information helped Haider track down the source of the stories: the disaffected village health worker, Razzak. Unbeknownst to BEST, Razzak had long been a distributor of water filters in Laksam. When BEST began to distribute the free UNICEF filters, Razzak saw his business dry up. He hadnt expected the researchers to be able to distribute filters for free. Recalls Haider: It was beyond his thinking, because he sold the filters for 3,500 taka to 5,000 taka, a lot of money in Bangladesh. But at the time, Razzak didnt complain about the dent in his business. Rather, he said that we were doing a great job, Haider says. He said the fact that people are getting filters free of cost is great. We could not predict what he was thinking. Haider also learned belatedly that Razzak in previous jobs had allegedly stolen drugs and sold them on the black market, and charged previous study participants for drugs.

In fact, Razzak was resentfulespecially after his dismissal. He had tipped off the press to his perverted version of BESTs activities. He also found other water filter merchants willing to line up behind him. With his strong family and business connections in the area, he began to turn community sentiment against the BEST project. Says Haider:

He had a plan to bring down the program. He also went to local political and religious leaders. He persuaded two of the local religious leaders to speak against the program during Friday prayers, warning listeners they would not go to heaven if they participated in the study.

Negative press

By mid-April, Razzaks campaign began to yield results. Bangladesh at the time was under an army-backed caretaker government. BEST opponents sent copies of the negative press to the local army base. That was troubling, but the worst was the effect on participants: a number of them expressed loudly their intention to withdraw from the study. Our participants said they would withdraw. That would have been devastating, Haider says. It was a very crucial moment. We were under very big pressure.

While relatively few of the 1,200 BEST subjects in Laksam actually threatened to withdraw, the publicity was highly damaging. As the situation escalated, recalls Parvez, we really became nervous because we didnt want to stop this important trial, and we also thought of the safety of our staff, some of whom had received threats. [32] Nor was there much support from local authorities, he adds: "Even if the local health authority wanted to help us, they really could not go against the will of the local political elite. Their position was very neutral. But at the same time we had a feeling they were much more siding towards [the local elites] because if you think of the power struggle, those guys were more powerful than us."

Superfund-Bangladesh Project Director Islam says the situation became even more confused when local reporters, who had started the controversy, made it clear that positive coverage could be bought. They wanted cash, because many other NGOs, when they have any problems, they just pay something under the table to the journalist, he recalls. BEST, however, was not willing to do that.

Matters came to a head for Ahsan and Parvez when an anonymous correspondent in Bangladesh emailed complaints about BEST to the presidents of the University of Chicago and Columbia and the dean of the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia, as well as the senior researchers. [33] The researchers found it disconcerting to see the campaign to discredit them brought to their institutional backyards. This prompted Graziano and Parvez to contact Columbia Associate General Counsel Edward Silver. With Silver on speakerphone in Grazianos office, the two explained the situation in Laksam and fielded the lawyers questions. Parvez recalls:

He wanted to know about BEST, how it was run. He said the university would get involved if there was a liability issue, if anyone was planning to sue. It was nerve-wracking at the time.

On the ground in Bangladesh, Islam decided it was time to confront the criticism head on. He called a press conference for May 8, 2008. The BEST team had to decide who should speak for the researchers and explain the study. They also considered whom to invite onto a panelwhich local officials with credibility could vouch for BEST? The public health researchers were not trained in managing a public relations crisis, and yet there was no one else to handle it. As Parvez puts it:

I was not ready for this. You have to be very careful and ready for unexpected things to happen. Its hard to really draw a boundary. How many outside people do you involve into your projects?A lot of times, that can damage what youre trying to do.So you have to [introduce yourself and explain your activities], but at the same time, you have to have some sort of boundary. You have to maintain a working relationship, but at the same time, you dont get them involved in your project. These things arent covered in any manual. It cost us sleep.

Faruque Parvez explains how to be prepared for the unexpected.

[30] Not Drugs But Arsenic-Free Water Imperative, The Daily People's View, Chittagong , March 02, 2008.

[31] Hundreds Affected by Arsenic Exposure; Foreign Organizations Provide Help, Daily Dinkal , May 8, 2008.

[32] Authors' interview with Faruque Parvez on January 19, 2012, in New York City. All further quotes from Parvez, unless otherwise attributed, are from this interview.

[33] No one involved had retained a copy of the email.