Room with a (Disturbing) View

From his glass-walled office, Smith could look out at the newsroom—an open space filled with sounds of clicking keyboards and ringing phones. To his ever more skeptical view, the newsroom editorial process seemed to have evolved to actually impede efficiency. For example, the online team worked from one corner of the newsroom and operated as a separate entity from the rest of the group. Editorial assistants hand-carried faxes and deposited them in reporters’ and editors’ in-boxes on their desks, where the pages often sat for days, often because no one knew they were there.

From his glass-walled office, Smith could look out at the newsroom—an open space filled with sounds of clicking keyboards and ringing phones. To his ever more skeptical view, the newsroom editorial process seemed to have evolved to actually impede efficiency. For example, the online team worked from one corner of the newsroom and operated as a separate entity from the rest of the group. Editorial assistants hand-carried faxes and deposited them in reporters’ and editors’ in-boxes on their desks, where the pages often sat for days, often because no one knew they were there.

Looking at this, Smith worried that readers would increasingly decide that the daily paper offered too little news too late. If that happened, he feared the paper would be forced to downsize, which in turn might force it out of business—as had happened at other publications. “If we weren’t efficient, we were going to lose the ballgame,” Smith says. “We simply wouldn’t have enough people to deliver a product that was sufficiently differentiated in the marketplace to survive... In journalism, you can’t cut your way to prosperity.”

Listen to Smith’s discussion on risk.

Smith and his team were fortunate that Hearst was a privately held company. Unlike public companies with their focus on short-term financial results, Hearst could make decisions about the newspapers it owned without pressure from stockholders to steadily increase the value of shares or dividends. It meant freedom to take risks, to strategize and set long-term targets with enviable flexibility. But no one knew what the strategy should be.

Role models? In late 2005, hoping to find a role model, Smith launched his own in-depth investigation of other newspaper websites. From his computer, Smith read online the Miami Herald , the Los Angeles Times , the Washington Post , and others with content-rich, vividly illustrated websites. Some used audio, others were experimenting with video. “I saw the Miami Herald and the Los Angeles Times with all these fabulous multimedia platforms,” he says. Some he admired; others, such as a piece by the Los Angeles Times on oceans , he thought readers would ignore. “The question was, to what extent were readers going to sit there and go through a multimedia presentation on this topic?” Smith says.

Smith also researched what wealthier, larger papers had done to reorganize their newsrooms to accommodate the Web, and whether that had persuaded advertisers to transfer their advertising dollars to the website. The Washington Post , for example, had drawn industry attention when it restructured its newsroom to better serve its website. From what Smith could glean from industry research and in conversations with his colleagues across the country, it was still too early to tell. While there had been missteps, there were indications that advertisers, if not readers, would help pay for Web-based news.

Smith considered how these approaches could apply to his smaller circulation, regional newspaper. For one thing, he could not lose sight of the fact that fully 94 percent of the organization’s revenue continued to come from the print newspaper, and only 6 percent from Web advertising. Moreover, a January 2005 study had shown that 65 percent of

Times Union

readers depended on it exclusively for their news; they did not subscribe to another paper. So for a large number of customers, the print product was far from irrelevant.

Smith considered how these approaches could apply to his smaller circulation, regional newspaper. For one thing, he could not lose sight of the fact that fully 94 percent of the organization’s revenue continued to come from the print newspaper, and only 6 percent from Web advertising. Moreover, a January 2005 study had shown that 65 percent of

Times Union

readers depended on it exclusively for their news; they did not subscribe to another paper. So for a large number of customers, the print product was far from irrelevant.

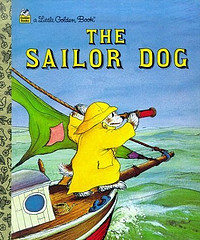

He likened his role at the paper to the captain of a ship, and felt like the character in a children’s book he kept in his office. But unlike a captain capable of plotting and changing the ship’s course, Smith felt he had charge of an assembly-line factory; in fact, the paper was registered as a factory with the New York Department of Economic Development. “It’s like the Ford production line model,” Smith says. “You put on the nut on top of the bolt, and then somebody puts the next nut on top of the next bolt.” Smith felt the ship needed to be turned around quickly, even if that meant some mistakes would be made. “You may not have figured out exactly what your precise proper tack is to get where you’re going,” he says. “But you eventually need to move, or you’re going to lose the wind.”