Personal Conduct Code

Assignments in Muslim countries required special precautions. Ordinarily, Addario wore modest clothing, long sleeved and loose fitting, along with other coverings customary to the region. She had worked in hijab (a simple headscarf to cover the hair) , in niqab (a veil that covered the head and face, but with an opening for the eyes), and in full abaya (a head-to-toe garment worn in some Arab states). Once she photographed street scenes in Kandahar from inside a full-length Afghan burqa, leaving the grid pattern of the mesh eye panel superimposed on every shot.

When custom demanded, as was usually the case in public places and if photographing Muslim men, Addario traveled with a man and worked with at least one male companion in plain view—a male colleague, a driver, a fixer, or a translator. She took special care in Afghanistan, where Muslim norms were especially conservative, once posing as the wife of New York Times ’ war correspondent Dexter Filkins, shooting pictures from behind a veil while Filkins interviewed a Taliban commander. That story, “Talibanistan,” garnered Addario and Filkins a place on the Times team that won the 2009 Pulitzer for International Reporting.

Besides providing access to places women did not usually go, such surrogate husbands and brothers provided some protection against the sexual harassment she encountered in the Middle East, especially in Pakistan. Like most female journalists reporting from Muslim countries, Addario dismissed the occasional crude remarks, lewd gropings, and verbal threats she received as occupational hazards: distasteful but unavoidable, nothing to make a fuss over. “I’m not gonna complain every time a guy grabs my butt,” she later told a magazine. “My editors are never gonna send me anywhere if I do that. If women are all of a sudden complaining all the time about getting sent to Pakistan, then if I were an editor, I probably wouldn’t send a woman either.” [9]

For other, more worrisome situations, Addario had developed an appeasement strategy. She tried to play for sympathy, and apologized no matter the circumstances. She tried to defuse tension by being submissive, pleading and crying. She emphasized that she was married, because Islamic law forbade touching another man’s wife. She never argued, and she never fought back . “In my experience, when a Western woman is very strong and outspoken and screaming and yelling, it is very counterproductive in terms of the reaction you get from Arab men,” Addario says. “Whereas, if you show weakness and you cry and you say ‘I’m scared, help me,’ then generally you get a much more positive response.” [10] This approach had served her well in all manner of difficulty, including an eight-hour detention by armed militants outside Falluja, Iraq, in 2004.

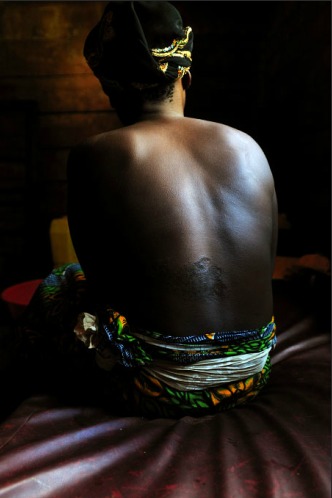

Sexual violence was a subject Addario knew well, but had never personally experienced. Over the years, she had reported on child rape, wife beating, honor killings, self-immolation, and violent punishments imposed on women. In a photograph that attracted widespread attention, she depicted an Afghan teenager whose Taliban husband cut off her nose, ears, and hair after she dared to run away from his daily beatings. In the Democratic Republic of Congo , soldiers and rebels alike raped thousands of women and girls as a weapon of war.

The violence Addario witnessed disturbed her. “While working in the Congo, I spent 10hours a day for two weeks talking with women who were victims of sexual assault and unimaginable violence,” Addario told American Photo . ”Each woman’s story was more violent and raw than her predecessor’s. On the final day of that assignment I was a complete basket case, crying all the time and so sad. And I thought, my life is great compared with these poor people. What right do I have to cry?” [11]

A Congolese girl's scars from sexual violence

Photo by Lynsey Addario

The MacArthur prize, popularly called a “genius grant,” was an extraordinary honor conferred on a handful of people each year. The recipients were selected for their creativity, originality, insight and “exceptional promise.” [12] The MacArthur Foundation cited Addario’s work in Afghanistan, Iraq, Darfur, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, praising her rigorous journalistic approach, her artistic eye, her ability to gain access to people and places often closed to outsiders, and her pursuit of images that told powerful stories in unexpected ways. [13] The award came with a $500,000 cash prize and no strings attached—except, perhaps, the expectation that the recipient “make important contributions in the future.” Honors . When Addario got the call to go to Libya, she was 37 and coming off a two-year roller-coaster ride. In May 2009 (a month after winning the Pulitzer), she broke her collarbone in a car accident in Pakistan that killed her driver and seriously injured another journalist. In July 2009, she married Paul de Bendern, Reuters’s New Delhi bureau chief, in a cathedral wedding in France. Two months later, just back from covering the presidential election in Afghanistan, she learned she had won a MacArthur fellowship.

Addario told interviewers that the award and the money wouldn’t change much for her. “I don’t think I’ll work any less!” she laughed. [14] In fact, in 2010 she produced a series of photo essays on earthquake orphans in Haiti , tuberculosis patients in India , and female soldiers serving with the US armed forces in Afghanistan . In September, Oprah Winfrey included Addario on her annual list of 20 Most Powerful Women in the category “Bearing Witness.” [15] She finished the year with a collection of photos in National Geographic documenting the lives of Afghan women, including some who had tried to escape domestic violence by setting themselves on fire. “I hope that my work helps people,” Addario says. “That's the thing that drives me and keeps me going.” [16]

To see more of Addario's work, visit her website .

[9] Abigail Pesta, “From the Front Lines of Libya,” Marie Claire, June 6, 2011. See: http://www.marieclaire.com/world-reports/news/photojournalist-lynsey-addario

[10] Author’s telephone interview with Lynsey Addario on November 29, 2011. All further quotes from Addario, unless otherwise attributed, are from this interview.

[11] Bedick, “Photography on the Front Line.”

[12] The MacArthur Foundation, “About the Fellows Program.” See: http://www.macfound.org/site/c.lkLXJ8MQKrH/b.4536879/k.9B87/About_the_Program.htm

[13] MacArthur Foundation, “2009 MacArthur Fellows: Lynsey Addario,” September 2009. See: http://www.macfound.org/site/c.lkLXJ8MQKrH/b.5457999/k.92D9/Lynsey_Addario.htm

[14] Bedick, “Photography on the Front Line.”

[15] “O, the Oprah Magazine Announces the 2010 O Power List,” O, The Oprah Magazine, September 13, 2010. See: http://www.marketwire.com/press-release/o-the-oprah-magazine-announces-the-2010-o-power-list-1317695.htm

[16] Pesta, “From the Front Lines of Libya.”